Everything is the same and everything is different

-Gertrude Stein

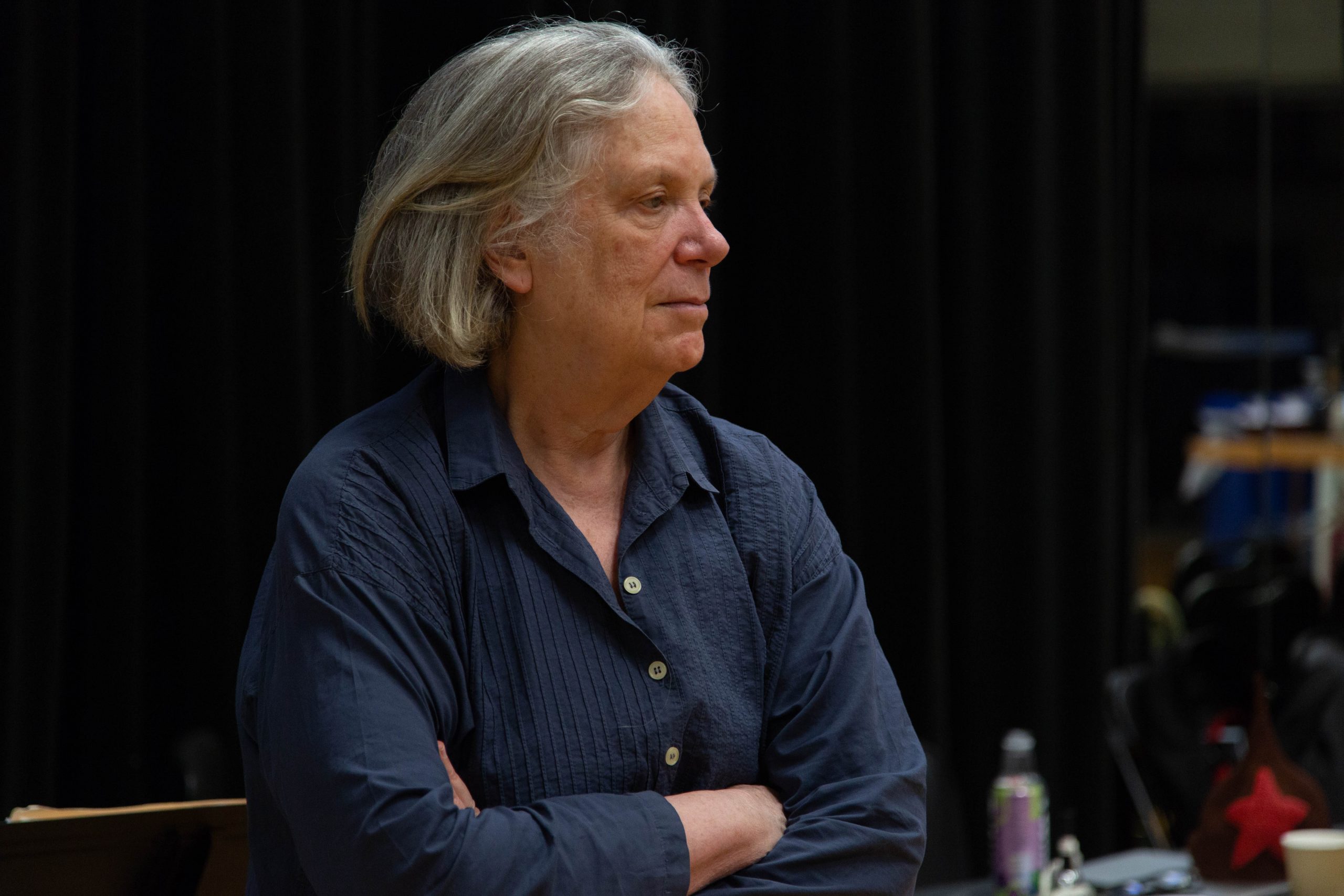

The composer David Lang has written a new music work based upon Gertrude Stein’s lecture Composition as Explanation. The Chicago music ensemble Eighth Blackbird commissioned the piece, and they will perform it. I was delighted to be invited to direct. The combination of these 21st Century musical pioneers taking on Gertrude Stein’s undeniable genius is thrilling. We will premiere the piece at Duke Performances in North Carolina on February 25th, 2022.

As a theater director, I have been deeply influenced by the “how” of Gertrude Stein’s writing and also by her example. In fact, as artistic parents, I chose Gertrude Stein to be my mother and Bertolt Brecht to be my father. Stein’s life and writing have always exerted a magnetic force on me.

My involvement with Stein began when I was in college. At first, I was fascinated by her life, which seemed intensely romantic. I began by reading her most accessible work The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas which drew a picture of a life that she both invented and then savored. Stein was an ex-pat, an American living in Paris, carving out a life with her same-sex partner Alice Toklas. I visualized their Paris salon on Rue du Fleurus, her art collection and her association with the cutting-edge Avant Garde who she attracted, inspired, and galvanized. I hungrily read what others wrote about her and stared at archival photographs of her life and her circle of friends. And I began in earnest to follow the tricky trajectory of her writing.

When I first moved to New York, I was thrilled to be invited to take part as a reader in the annual New Year’s Eve reading of Stein’s epic novel, The Making of Americans at the Paula Cooper Gallery in Soho. Between 1975 until 2000, the gallery presented this much-celebrated event, a non-stop performance that required approximately 48 hours to read the book in its entirely. Audiences came and went, often falling asleep on the wooden floors of the gallery as the readers read. Each reader had a slot of one hour on a slightly raised platform next to another reader. Every half-hour one of the readers rotated off and another one joined. My two partners that night (drum roll please): John Cage and Lucinda Childs.

I could feel how Stein’s writing, her syntax, her use of repetition and variation, and sameness and difference began to affect the way I collaborated with actors to stage plays. Stein broke literature down, like a cubist painting that reveals each side differently. She worked intricately with shapes, sounds and rhythms. It seemed to me that Gertrude Stein’s words were like people on a page, moving in a fluid concert of interaction. And her sentences seemed to be social systems, crowds moving across a landscape. I was able to transfer the incantatory musicality of Stein’s repetitions and syntax onto the stage through movement, shape, gesture, and stillness.

In 1984 I was invited by the remarkable producer Lynn Austin, the founder of Music Theater Group, to direct Stein’s The Making of Americans with music by Al Carmines, the founder of the Judson Church Poets’ Theater. This is when I first had the opportunity to translate Stein’s own written language directly into the parallel language of the stage, into the semantics of space and time. Much later, in the mid 1990’s, I directed a production of a play entitled Gertrude and Alice; A Likeness to Loving, with the real-life couple Lola Pashalinksi and Linda Chapman portraying Gertrude and Alice. These direct encounters with Stein were wonderful.

I feel Gertrude Stein in the ecology of my being; she is part of me. There is no doubt that she can be challenging to readers and to audiences. Her ideas were radical, even in her own time, and required digestion. Her writing still demands intense engagement. But when the receiver is connected, a remarkable emotional syncopation can arise between reader or audience and page or stage. Deeper levels of meaning and layers of experience are always available if you choose to go on the journey. But you have to choose, otherwise, the experience can be disorienting. Gertrude Stein requires concentration and patience.

In direct contrast to her contemporary James Joyce, Stein did more with less. Joyce’s multi-layered work is marked by the amount of complexity implemented in the act of writing. He created new dream languages, a mixture of existing and invented words in an unstoppable stream of consciousness. In contrast, Stein, rather than inventing new words, telescoped her vocabulary into the minimum number of words to express the widest sentiments. It is the arrangement of a very defined number of words that creates the meaning and the reader’s experience.

From Stein I learned how to do more with less. I translated her minimalist approach to writing to my own practice of staging. She could express huge feelings and complicated ideas while drawing upon an enormously limited vocabulary. I, in turn, limited the number of shapes, gestures, sounds, and patterns in any one production and learned to celebrate repetition. Stein showed me how patterns and repetitions can create additional layers of meaning for an audience.

During the winter of 1925-26 Gertrude Stein wrote Composition as Explanation in which, for the first time, she discussed her approach to writing and the concerns that shaped her early work. The irascible British poet Edith Sitwell, confident that a public appearance by Stein would go a long way to cultivate a wider audience for her work, convinced her to deliver the piece as a lecture to the Cambridge Literary Club and later that following summer, at Oxford University. Composition as Explanation was eventually published by Leonard and Virginia Woolf’s Hogarth Press.

Apparently, before delivering the lecture, Stein suffered intense stage fright. Although she was aware that the invitations to lecture presented an opportunity to share her approach to writing with a new generation, Stein was frightened by the prospect of performing in front of a large audience. In the end, her reputation as an eccentric writer drew large audiences, she found her footing as a public speaker, and both lectures turned out to be a great success. Nobody had heard anything like it before.

As a lecture, Composition as Explanation is clearly designed to lead to deeper levels of understanding of her writing through an experiential encounter with non-linear language. Stein demonstrates how removing the meaning of a word through repetition could then revive its meaning, reifying the word all over again, but without its conventional associations. Edith Sitwell described how Stein “threw a word into the air,” thereby freeing it of past associations. In the same lecture, Stein also examines how the world can be seen by different generations as a framework that can define and re-define perceptions, and which can apply to the art of living as well. She discusses her embrace of the “prolonged present” and the “continuous present,” rather than the traditional past, present, and future tenses. She also describes her approach as “using everything” and “beginning again.”

In sync with the inventions and discoveries of her modernist era, all of Stein’s non-traditional prose is imbued with her feeling for modern art (Braque and Picasso’s Cubism), innovations in science (Heisenberg’s Uncertainty Principle, and Einstein’s Theory of Relativity), psychology (Freud’s discovery of the unconscious), philosophy (William James and Henri Bergson), Darwin, Marx and so on. Her writing is not only melodic and meditative, but also poetic and philosophical, reflecting uncertainty, indeterminacy, and relativity. She predominantly used the present progressive tense in her work, creating a continuous presence. Based upon the body and on intuition, it is multi-sensory in its rhythmic qualities, idiosyncratic and playfully repetitive.

David Lang has translated Stein’s Composition as Explanation and her ideas into a musical experience for audiences. As a composer, he clearly takes inspiration from how Stein handled words and sentences. The music also reflects Stein’s notions about how “things” or individual elements do not change over time, rather, what changes is the relationship between those elements. According to Stein, composition is simply the arrangement of these elements (“things”) or words. She suggests that we construct new meanings always with pieces of the past, elements of the old. But throughout the lecture as well as in much of her writing, this experience happens in the present tense.

As a director my task is to bring a context to the event of the performance. For Composition as Explanation, David Lang proposes that the musicians not only play his intricate and inventive music, but that they also speak and sometimes sing Stein’s text. He wants to see the members of 8th Blackbird do more than simply deliver the music to the listener. He is interested in developing a new kind of musical artist, one with the formal training of actors on the stage. For our production, I imagine that each musician is a lecturer as well as a cubist avatar for Gertrude Stein. They do not impersonate her, rather, each is responsible for delivering her message in their own way. What might Gertrude Stein’s first-ever lecture have been like? Is this Gertrude Stein’s 1926 version of a TED Talk? In addition to allowing the music to be heard with great clarity, I am interested in how the evening can feel like a great multifaceted lecture, as well as a shared communal event.

Apparently, at one of Gertrude Stein’s actual lectures, two men came to bait her, and they aggressively took turns asking her questions. One of them asked: “Miss Stein, you say that everything being the same, everything is always different. How can that be so?” She replied: “Consider the two of you. You jump up one after the other. That is the same thing and surely you admit that the two of you are always different.” One of the men said “touché” and the lecture came to an end.

Recent Comments