Blog #142 – December 2022

I share an ongoing friendly debate with Elizabeth Streb, the remarkable creative force behind the STREB Extreme Action Company. She insists that she does not use metaphor in her work. I try to impress upon her that, in my eyes, all theater is metaphorical. But for Elizabeth, when a body crashes into glass, it is simply that: a body crashing into glass. When I look at STREB’s work and see one of the dancers crashing into glass, I experience and interpret the act as a metaphor for the struggles that we humans undergo daily. The crashing into glass expresses the many complex feelings that I experience while moving through life. And the performance of crashing into glass becomes quite meaningful to me. Metaphor.

Theatrical language is a particular kind of iconic communication and metaphor is one of its essential building blocks. I believe that learning how to work with metaphor is crucial for playwrights, directors, designers, and dramaturgs. Metaphors are beautiful and complicated ideas expressed simply and eloquently through analogous representations. They can be powerful tools for expressing complex ideas in a memorable way.

Textual metaphors abound in dramatic literature. In Arthur Miller’s The Crucible, for example, 17th century New England, stands in for, or is a metaphor for, 1950s McCarthy era. Visual metaphors are also plentiful. An empty chair can stand in for someone who is missing. The Statue of Liberty might be analogous to idealism. These emergent meanings are always dependent upon context and arrangement. In the right context and arrangement, a broken mirror might symbolize separation or insecurity. An actor backing slowly into a corner can express the concept of anguish.

The key role of metaphor is to carry information on multiple levels that, if presented directly, might be too complex or difficult to handle. Theater and opera directors should understand textual and visual metaphor but also must be able to think of metaphors that are embodied in action over time. In rehearsal, we search for how the many meanings of the play can be contained within the languages of movement, shape, rhythm, gesture, space, and time. Winnie is buried in a mound of earth in Samuel Beckett’s play Happy Days, and as the play progresses, the dirt rises, covering more and more of her body all the way up to her neck. Metaphor. In Peter Brook’s 1960 production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream, a man and a woman suspended in the air, swing across the stage. Their swinging became a metaphor for and an expression of their love.

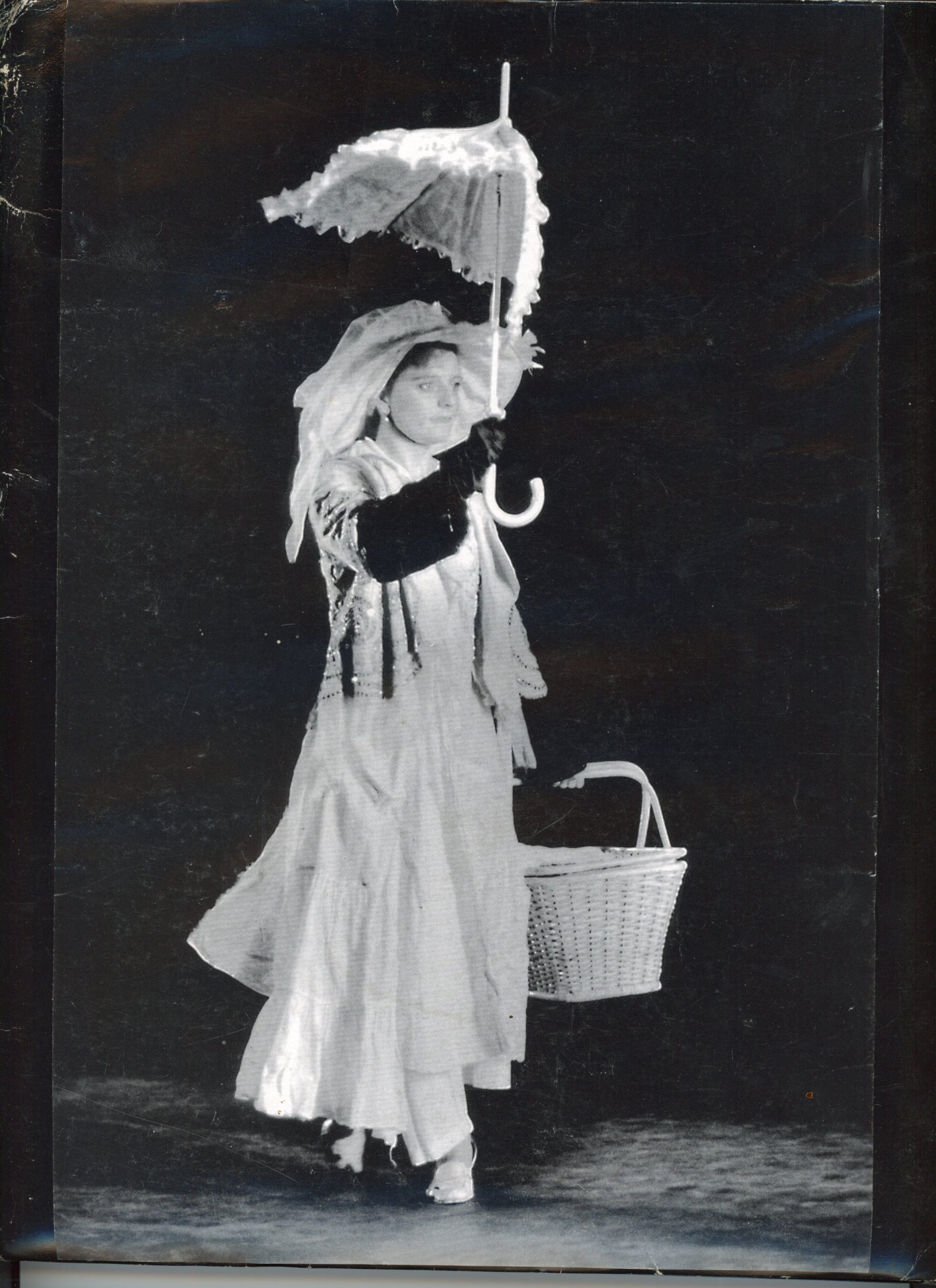

In the SITI Company production Small Lives Big Dreams, Kelly Maurer, who plays a character based upon Chekhov’s play Cherry Orchard, carries a tattered umbrella across the stage four times over the course of the play, from stage right to stage left. The umbrella gradually becomes a representation of human frailty in the face of overwhelming obstacles. The way that Kelly handled and moved the umbrella is what brought such poignancy to her metaphorical embodiment of complex feelings and meanings. But Kelly cannot act a metaphor; she plays the actions and the character. She cannot think about metaphor. If she did, all poignancy would evaporate.

At a post-show Q & A after a performance of Small Lives/Big Dreams, an audience member asked the actors how they function successfully in the midst of a production that is wildly imagistic and expressive. Will Bond, who played a character based upon Three Sisters, offered a resonant response. “As an actor,” he said, “I put all of my attention on the most human action available to me, which might be as simple as holding onto and sipping a cup of tea.”

While actors may avoid metaphor in their construction of poignant moments on stage, they do liberally employ imagery. These images enrich their inner experience and fill the body with energy and expressiveness. Their work is to create the elements which, with arrangement and context, may generate effective metaphors.

But ultimately, the metaphor is a message aimed at the mind of the interpreter, the audience. Metaphors are implicitly felt and recognized by an individual, rather than explicitly observed. They are tacitly related to the original stimulus, or arrangement of imagery, but demand an abstract understanding. Metaphors usually speak to the unconscious and ignite both parts of the human brain, creating a visceral, mind-body experience. Our brains are wired to make connections between symbols. The symbolic nature of a metaphor activates our right hemisphere, which can play with it, visualize it, and expand it. The verbalization of the metaphor requires the left hemisphere of the brain to make connections and then find words to describe it.

In 2019, Elizabeth Streb and I co-directed the STREB Company and SITI Company in a new production entitled FALLING & LOVING, with text by Charles Mee. Elizabeth had the brilliant but unusual idea of suspending about 60 buckets full of different kinds of what she called “guck” above the performers’ heads, each bucket with a string hanging down to the stage. Whenever a performer pulled one of the strings, a dose of the “guck” fell down upon their heads and bodies. In this case, the metaphor of falling was both literary and literal. Not only did the “guck” fall with increasing velocity and volume from above, but the performers whirled and fell while two heavy bowling balls, suspended from above, swung, pendulum-like, and with great force across the stage and towards the performers’ bodies.

Metaphors are a way to understand and experience one thing in terms of another. It is the metaphor that contains the meaning. What did FALLING & LOVING “mean?” I believe that the production captured the complexities of human love. Elizabeth Streb, who I admire for her courage and artistry, may skirt the subject of meaning via metaphor, but I celebrate it.

Recent Comments