The artist’s work is to lift people out of their usual sense of their own cosmos into a higher vision of what’s going on up there.

Peter Sellars

Some time ago, the director Peter Sellars said in an interview that due to the current state of the world, he found it necessary to load the stage with a great deal of stuff in order to finally arrive at one simple, unencumbered moment.

In this blog I want to explore the notion of layering, stacking, juxtaposing, and consciously creating multiple tracks on the stage. And I also want to address why the use of tracks can be so useful for theater.

One of the frequent misconceptions about the theater is the notion that the visual track should always match the aural track. In life, people’s actions rarely describe what they are saying at that moment. Usually, while they are saying one thing, they are doing something different. One person looking directly into another person’s eyes while speaking the words, “I love you” can be a beautiful expression of affection. But the words “I love you” are rarely spoken while looking directly into another person’s eyes. I would suggest that about 95% of the time, in life, the physical action is not a description of the spoken words. A person leaving home for the day throws the words “I love you” over their shoulder as they go out the door. This is an example of two separate tracks. The physical action, exiting while looking over the shoulder, is the visual track, and the words, or text, “I love you,” is the aural track. The two tracks work together, but in juxtaposition, to reveal the quotidian complexity of a love relationship.

When the theater experience feels disappointing and lifeless, it is often because the audience is constantly seeing the same thing that they are hearing. The layers of perception all agree with one another too often. The result is a kind of dullness. The sight of a couch in the middle of a living room set may lead to an entire evening of watching actors rotate around the couch, attempting to express themselves directly to one another, gesturing in repetition of the words.

Far too often actors will default to doing what they are saying. With luck, and after a long rehearsal process, it is conceivable that more dynamic and diverse solutions can be discovered. But it is also possible to arrive at a rich multiplicity far more quickly by consciously separating the visual and aural tracks.

Occasionally in rehearsal I work with the actors to stage the physical actions of a scene separately from the text. Together, after studying the scene, we create a chain of actions that reveal information about the situation, the characters, and the relationships. It is only afterwards, once the chain of actions, or visual information, is firmly in place, do we introduce the text, the speaking. The co-incidences that arise when the two tracks are put together never ceases to amaze me. Because human beings are inveterate story tellers, the disjunction between the physical actions and the spoken dialogue create a challenge for the actors who can find innovative ways to connect the two.

On the surface there has to be something accessible. The mystery is on the surface. Underneath it can be complicated, about a million things. The surface has to be about one thing first.

Robert Wilson

Over the past century, film, in particular with its innovations in montage and editing, has influenced the trajectory of the theater in ways that have been useful and even transformational. The mechanics of film clearly illustrate the concept of tracks. Because in film the visual track is literally physical and separate from the soundtrack, the split is always present in the creation of story and meaning. The filmic experience is also enhanced by techniques such as cross-cutting, jump-cuts, cut-aways, match-cuts, close-ups, long-shots, panning shots, etc. All of these techniques can be translated into the language of the stage and to the movement of bodies in space. Assembling shots, or in the case of physical theater, moves, into a coherent sequence requires an aesthetic sensibility and also a semiotic one.

Montage, in particular, can be highly advantageous to the theater. A montage presents a collection of diverse images to the audience all at once, so that the overall impression has the possibility to become much richer than simply showing a single image or element. Early Russian filmmaker Sergei Eisenstein described montage as a collision between individual images, resulting in a third image or new idea. Bertolt Brecht called the technique “connecting dissimilars”

The conflict between the tracks creates the meaning. In film, Shot A + Shot B = New Meaning C. Sergei Eisenstein, in an essay that he wrote about montage in 1929, offered concrete examples of juxtaposing images in service of generating meaning:

Eye + Water = Crying

Door + Ear = Eavesdropping

Child + Mouth = Screaming

Mouth + Dog = Barking

Mouth + Dog = Singing

In the United States, the theater generally tends to privilege psychology as the main ingredient of drama. But at best, psychology is only one layer, or track, in a given moment. Often it not even the most interesting. In the theater, it is possible for many layers of reality to happen at any moment. Through the use of montage, we can learn to amplify meaning onstage by layering tracks into a series of contrasting bits that produce an immaterial concept not exactly present in each of the merged images. It is possible to weave together bits to explore meaning, while always keeping the flow of information accessible for an audience.

In the theater, the default choice is too often that sound underscores what the action is already doing. Using contrasting tracks, it is possible to heighten the experience of a performance. Like music, which can be upbeat and joyful while the lyrics are sinister and dark, the theater can run multiple and conflicting tracks simultaneously. A violent argument can be overlaid with the sweet sounds of birds mating to great effect. Martin Scorsese, for the film Raging Bull, scored the bloodiest fight scenes with the gentle and soaring Intermezzo of Pietro Mascagni’s Cavalleria Rusticana. The experience of the music is elevating, but we are watching a man who is a sad fraction of what he was, degraded and worthy of pity. The result of this juxtaposition is part of what makes the audience’s experience of the film so resonant.

But there are even more radical ways of working with tracks in the theater to bring layers of complexity and deeper meaning to a theatrical event. John Cage and Merce Cunningham often worked together in such a way that only on opening night did the Cunningham dancers hear the music that Cage had composed for a given piece of choreography. In that spirit, I have often found it useful to create completely separate tracks that seem to have little to do with each other and then put them to together to explore certain themes and to discover new resonances.

For example: In 1995, I worked with SITI Company to devise a new production entitled Going, Going Gone, which premiered at the Humana Festival of New American Plays and toured extensively afterwards. At the time I wanted to explore the newest and most significant developments in quantum and astral physics, but I knew that the audience needed to be distracted by a strong story in order to be open to receive the somewhat challenging scientific text and ideas. This disjunction is what physicists called “fuzzy logic” wherein one has to look away from the thing being attended to in order to begin to perceive it.

We began by rehearsing an edited version of Edward Albee’s Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf and created an entire physical score, with all of the play’s psychological subtleties. It was only after the play was fully staged in such a way that the story was visually clear from moment to moment, that we discarded Albee’s words completely and replaced them with text gathered from the writings of many scientists and philosophers on subjects such as relativity, Heisenberg’s Uncertainty Principle, string theory, Bell’s Theorem, complementarity, parallel universes and so forth. These ideas were presented laterally as opposed to linearly. It was through the accumulation and juxtaposition of these notions that patterns and even understandings emerged. For the audience, it was not a direct act of grasping, but rather a slow appreciation of how these new scientific notions might work in relation to our own perception of reality and how we live our quotidian lives.

More recently, this past summer during the final Saratoga/Skidmore intensive training that we conducted via Zoom, we focused the composition class on the exploration of separate tracks. The participants ate it up and made spectacular work. After two years of isolation, using digital technology to meet, they were ready to fully exploit the power of what Brecht called “connecting dissimilars.”

But all of the layering, multiple tracks and juxtaposition must ultimately be in service of what art does best: bringing us closer to something true. Peter Sellars’ comment about loading the stage with a great deal of stuff in order to allow for a simple, unencumbered moment reminds me of the composer Gustav Mahler’s symphonies, in which often, after much sturm und drang, all of the sound falls away except for a single, long, sustained note. The effect can feel palpable and deeply meaningful. The complexity of the preceding storm of sound then makes the single note momentous and effective.

Overloading can also be hazardous. Marshall McLuhan borrowed the phrase “information overload equals pattern recognition” from IBM. He said, “faced with information overload, we have no alternative but pattern recognition.” This is how advertising works. You watch television with its fast-paced edits and ubiquitous advertising, and then you have no idea why the next day in the grocery store, you reach for the Tide detergent. Your conscious mind been overloaded leaving you with a message, in this case in service of corporate avarice.

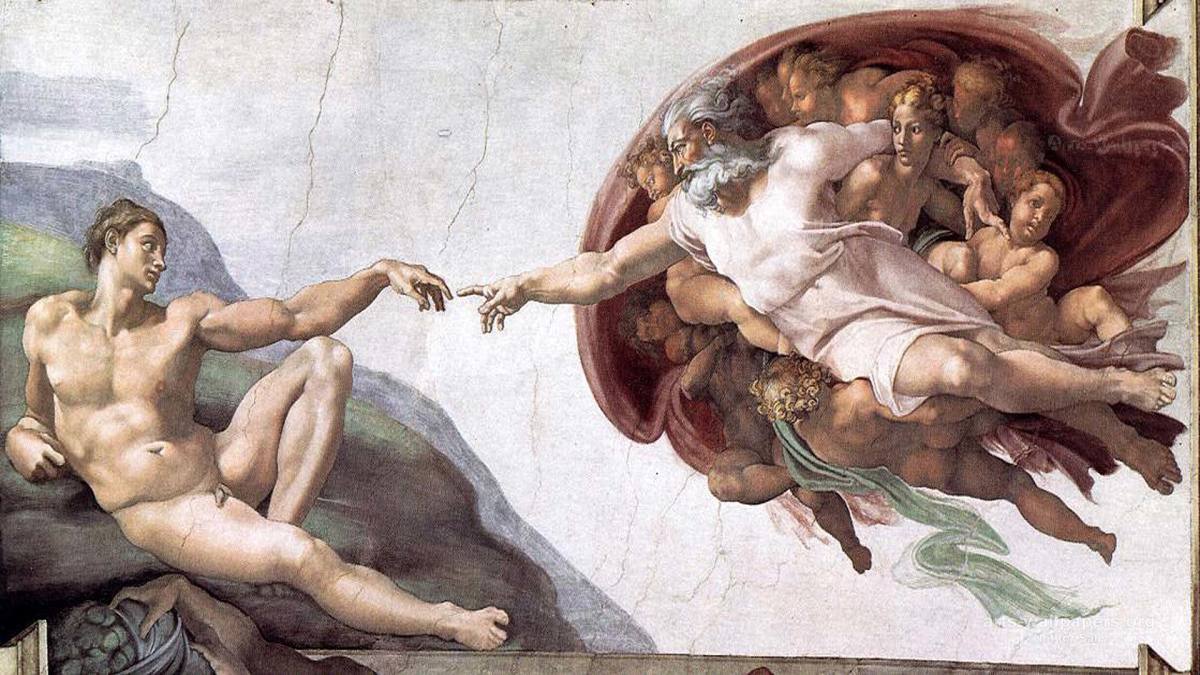

According to some neuroscientists, the imagery in Michelangelo’s’ ceiling in the Sistine Chapel is so dense and concentrated that amidst the sensory overload, the conscious mind of the viewer breaks down and recognizes patterns. Perhaps the message is religious, inspiring awe and a belief in the divine. Or possibly the meaning of the masterpiece is even more complicated and unexpected. Some researchers contend that Michelangelo hid the human brain stem, eyes, and optic nerve of the man inside the figure of God directly above the altar. The voice box of God rises out of the man’s brain stem, expressing the direct juxtaposition of God and the human brain. Perhaps the meaning in the Sistine Chapel is not of God giving intelligence to Adam, but rather that the intelligence and observation of the human brain makes it possible for humans to connect to God without the necessity of the Church as an intermediary.

All of this may feel quite heady, but the following question is worth considering: Is it possible to create theater that uses the notion of tracks, montage, layering, cross-cutting, and juxtaposition so that when the moment finally arrives, when one human looks in directly into the eyes of another and says, “I love you,” everything else falls away except for this one gorgeous moment of grace and simplicity?

Recent Comments